CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE

4. On this journey, I defined the Mekong very broadly. At times I

ventured one or two hundred miles from the water itself to chase down

ideas or check on stories I had heard. In southern Yunnan, there are few

villages along the river itself, and it was often necessary to wander

off the river to find a place to stay. Early mornings here brought a

magical light. Off tiny rural roads, there were endless miles of

terraced paddies, and in the sun they invariably reminded me of those

ostentatious staircases in Busby Berkeley musicals down which sequinned

show girls pranced, a cultural reference that never quite made it into

translation in conversations with people I met there.

4. On this journey, I defined the Mekong very broadly. At times I

ventured one or two hundred miles from the water itself to chase down

ideas or check on stories I had heard. In southern Yunnan, there are few

villages along the river itself, and it was often necessary to wander

off the river to find a place to stay. Early mornings here brought a

magical light. Off tiny rural roads, there were endless miles of

terraced paddies, and in the sun they invariably reminded me of those

ostentatious staircases in Busby Berkeley musicals down which sequinned

show girls pranced, a cultural reference that never quite made it into

translation in conversations with people I met there.

5. Southern Yunnan is quite mountainous, not in the Himalayan

sense, but dense with bulky hills through which only the occasional

narrow road winds, roads usually unpaved, but on occasion paved with

cobbles that are still laid by hand today in rural parts of China. One

morning driving through the hills in a dense misty fog the road surfaced

above the clouds and before me lay a white sea dotted with islands, the

tops of nearby hills. It was intensely quiet and totally empty, as if I

were stranded on some celestial island alone.

5. Southern Yunnan is quite mountainous, not in the Himalayan

sense, but dense with bulky hills through which only the occasional

narrow road winds, roads usually unpaved, but on occasion paved with

cobbles that are still laid by hand today in rural parts of China. One

morning driving through the hills in a dense misty fog the road surfaced

above the clouds and before me lay a white sea dotted with islands, the

tops of nearby hills. It was intensely quiet and totally empty, as if I

were stranded on some celestial island alone.

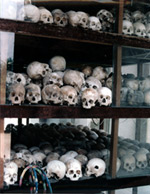

6.

For nearly four years, Cambodia was brutalized by the Khmer

Rouge, a regime that turned on its people, murdering nearly 2 million of

them before they were driven from power by the Vietnamese in 1979. In

the years that followed, endless killing fields were unearthed, places

where the Khmer Rouge had taken their victims and massacred them. In

Siem Riep, near the ancient temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, a bit

off the tourist roads, there is a small Buddhist monastery and in the

courtyard, a glass ossuary contained the skulls of Khmer Rouge victims

that were dug up from nearby mass graveyards. It was, as is much of

Cambodia, a terrifying memorial, a symbol of the horror through which

the country had gone, and perhaps a warning to the future.

6.

For nearly four years, Cambodia was brutalized by the Khmer

Rouge, a regime that turned on its people, murdering nearly 2 million of

them before they were driven from power by the Vietnamese in 1979. In

the years that followed, endless killing fields were unearthed, places

where the Khmer Rouge had taken their victims and massacred them. In

Siem Riep, near the ancient temples of Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, a bit

off the tourist roads, there is a small Buddhist monastery and in the

courtyard, a glass ossuary contained the skulls of Khmer Rouge victims

that were dug up from nearby mass graveyards. It was, as is much of

Cambodia, a terrifying memorial, a symbol of the horror through which

the country had gone, and perhaps a warning to the future.

NEXT