|

|

Photo © Brice Hammack

|

|

|

Newly Discovered Primary Sources

Reinterpreting History: How Jesse James Differs from Standard Accounts

Photographs

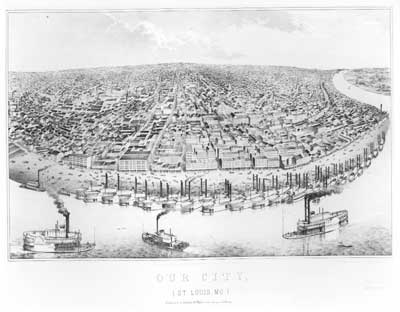

THE ST. LOUIS WATERFRONT, 1859

In 1859, the year that this engraving was published, the nation was slouching toward civil war. In the widening division between North and South, no state faced such deep internal divisions as Missouri, the northwesternmost bastion of slaveholding. This view of St. Louis's Mississippi riverfront captures some of the reasons why. The eighth largest city in the country, it was home to tens of thousands of German and Irish immigrants, boasting the highest proportion of foreign-born of any American city, including New York. Slaves made up fewer than one out of ten people in the city, which was represented in Congress by antislavery politician Frank Blair. This engraving reveals the urban density and frenetic commercial activity that made the city an extension of the market-oriented, free-labor North.

And yet, the scores of steamboats clogging the levee also hint at the state's close ties to the South, and its dependence upon slave labor. Many of these vessels churned between St. Louis and the state's Missouri River towns, collecting hogs, mules, corn, hemp, and tobacco raised primarily by slaves. Other boats puffed downstream to New Orleans, their decks overflowing with rope, bagging, cigars, livestock, manufactured goods, and foodstuff designated for sale in the South. Many of St. Louis's oldest and richest families were fierce advocates of secession. Business-minded, Southern-minded--St. Louis reflected the paradoxes facing this border state as North and South split apart.

Next Photo.

|

|

|