|

|

Photo © Brice Hammack

|

|

|

Newly Discovered Primary Sources

Reinterpreting History: How Jesse James Differs from Standard Accounts

Photographs

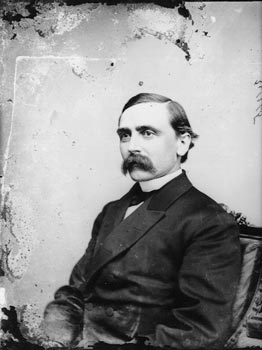

ADELBERT AMES

On September 7, 1876, the James and Younger brothers, along with Clell Miller, Samuel Wells (alias Charlie Pitts), and William Stiles (alias Bill Chadwell) tried to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota. The raid was an unmitigated disaster; in the end, only Frank and Jesse James escaped alive. For decades, an unanswered question lingered over the event: Why did the Missouri bandits stray so far from their hunting grounds, and especially so far North? The only explicit answer given by the outlaws seemed to be Cole Younger's comment, in his 1903 autobiography, that they chose Northfield because they had learned that Radical Republican congressman Benjamin Butler and his son-in-law "J.T. Ames" (actually Adelbert Ames) had money in the bank. The great Jesse James biographer William A. Settle, Jr., dismissed the statement as a "rationalization," and most writers have accepted his judgment. But Younger made the same claim earlier in a narrative that was not written for publication; even more telling, immediately after the bandits were captured, Cole's brother Bob stated that they had come to rob Adelbert Ames, a declaration that has been overlooked in most accounts of the raid.

Why go so far to rob Adelbert Ames? His father-in-law Benjamin Butler was certainly unpopular among white Southerners, thanks to his stern rule of Union-occupied New Orleans during the Civil War. But Ames himself was an inviting target--a man who was virtually the direct opposite of Jesse James. Raised in Maine (and at sea) by his ship-captain father, Ames graduated fourth in the West Point Class of 1861, far ahead of last-place George Custer. He behaved so heroically at the first battle of Bull Run that he was later awarded the Medal of Honor. He went on to fight almost continuously throughout the war, from Antietam to Gettysburg (where he narrowly won the struggle to hold Cemetery Hill on the second day) to Fort Fisher. His first regimental command was the 20th Maine, which he whipped into shape; his protege and successor was the famous Joshua Chamberlain. After the battle of Gettysburg, the regiment presented its battered flag to Ames as a token of its appreciation.

After the war, Ames was assigned to Reconstruction duty in the South. Though a product of Eastern cosmopolitan culture, frequently given to elitism, Ames came to identify with the freed slaves. Reflective, articulate, driven by a deep sense of duty, he left the army to represent Mississippi in the Senate (alongside the nation's first black senator, Hiram Revels), then returned to lead the largely black wing of the state's Republican party by standing for governor (a race he easily won). Even Ames's harshest critics admitted that he was an honest and decent man, and his administration a frugal one. In 1875, however, increasingly violent white supremacist forces gathered in the Democratic party staged a carefully planned insurrection. Scores, perhaps hundreds, of African Americans died as the Grant administration refused to intervene with troops. With the legislature completely under the control of the Democratic party, with no prospect of federal civil-rights enforcement, Ames reluctantly resigned in 1876, joining his father and brother in the flour-milling business in Northfield, Minnesota.

Ames did not die until 1933, the last general on either side to pass away. In a curious footnote, his politically active, polymath daughter, Blanche Ames Ames, became enraged when John F. Kennedy libeled Ames in Profiles in Courage. She pestered Kennedy's office so peristently that the President finally asked her grandson, George Plimpton, to intervene.

Next Photo.

|

|

|