C H A P T E R 1

DÉBUTANTE

1757—1774

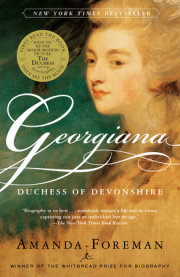

"I know I was handsome . . . and have always been fashionable, but I do assure you,” Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, wrote to her daughter at the end of her life, “our negligence and ommissions have been forgiven and we have been loved, more from our being free from airs than from any other circumstance.”* Lacking airs was only part of her charm. She had always fascinated people. According to the retired French diplomat Louis Dutens, who wrote a memoir of English society in the 1780s and 1790s, “When she appeared, every eye was turned towards her; when absent, she was the subject of universal conversation.” Georgiana was not classically pretty, but she was tall, arresting, sexually attractive, and extremely stylish. Indeed, the newspapers dubbed her the Empress of Fashion.

The famous Gainsborough portrait of Georgiana succeeds in capturing something of the enigmatic charm which her contemporaries found so compelling. However, it is not an accurate depiction of her features: her eyes were heavier, her mouth larger. Georgiana’s son Hart (short for Marquess of Hartington) insisted that no artist ever succeeded in painting a true representation of his mother. Her character was too full of contradictions, the spirit which animated her thoughts too quick to be caught in a single expression.

Georgiana Spencer was the eldest child of the Earl and Countess Spencer.* She was born on June 7, 1757, at the family country seat, Althorp Park, situated some one hundred miles north of London in the sheep-farming county of Northamptonshire. She was a precocious and affectionate baby and the birth of her brother George, a year later, failed to diminish Lady Spencer’s infatuation with her daughter. Georgiana would always have first place in her heart, she confessed: “I will own I feel so partial to my Dear little Gee, that I think I never shall love another so well.” The arrival of a second daughter, Harriet, in 1761 did not alter Lady Spencer’s feelings. Writing soon after the birth, she dismissed Georgiana’s sister as a “little ugly girl” with “no beauty to brag of but an abundance of fine brown hair.” The special bond between Georgiana and her mother endured throughout her childhood and beyond. They loved each other with a rare intensity. “You are my best and dearest friend,” Georgiana told her when she was seventeen. “You have my heart and may do what you will with it.”

By contrast, Georgiana–like her sister and brother–was always a little frightened of her father. He was not violent, but his explosive temper inspired awe and sometimes terror. “I believe he was a man of generous and amiable disposition,” wrote his grandson, who never knew him. But his character had been spoiled, partly by almost continual ill-health and partly by his “having been placed at too early a period of his life in the possession of what then appeared to him inexhaustible wealth.” Georgiana’s father was only eleven when his own father died of alcoholism, leaving behind an estate worth £750,000–roughly equivalent to $74 million today.† It was one of the largest fortunes in England and included 100,000 acres in twenty-seven different counties, five substantial residences, and a sumptuous collection of plate, jewels, and old-master paintings. Lord Spencer had an income of £700 a week in an era when a gentleman could live off £300 a year.

Georgiana’s earliest memories were of travelling between the five houses. She learnt to associate the change in seasons with her family’s move to a different location. During the “season,” when society took up residence “in town” and Parliament was in session, they lived in a draughty, old-fashioned house in Grosvenor Street a few minutes’ walk from where the American embassy now resides. In the summer, when the stench of the cesspool next to the house and the clouds of dust generated by passing traffic became unbearable, they took refuge at Wimbledon Park, a Palladian villa on the outskirts of London. In the autumn they went north to their hunting lodge in Pytchley outside Kettering, and in the winter months, from November to March, they stayed at Althorp, the country seat of the Spencers for over three hundred years.

When the diarist John Evelyn visited Althorp in the seventeenth century he described the H-shaped building as almost palatial, “a noble pile . . . such as may become a great prince.” He particularly admired the great saloon, which had been the courtyard of the house until one of Georgiana’s ancestors covered it over with a glass roof. To Lord and Lady Spencer it was the ballroom; to the children it was an indoor playground. On rainy days they would take turns to slide down the famous ten-foot-wide staircase or run around the first-floor gallery playing tag. From the top of the stairs, dominating the hall, a full-length portrait of Robert, first Baron Spencer (created 1603), gazed down at his descendants, whose lesser portraits lined the ground floor.*

Georgiana was seven when the family moved their London residence to the newly built Spencer House in St. James’s, overlooking Green Park. The length of time and sums involved in the building–almost £50,000 over seven years–reflected Lord Spencer’s determination to create a house worthy of his growing collection of classical antiquities. The travel writer and economist Arthur Young was among the first people to view the house when Lord Spencer opened it to the public. “I know not in England a more beautiful piece of architecture,” he wrote, “superior to any house I have seen. . . . The hangings, carpets, glasses, sofas, chairs, tables, slabs, everything, are not only astonishingly beautiful, but contain a vast variety.” Everything, from the elaborate classical façade to the lavishly decorated interior, so much admired by Arthur Young, reflected Lord Spencer’s taste. He was a noted connoisseur and passionate collector of rare books and Italian art. Each time he went abroad he returned with a cargo of paintings and statues for the house. His favourite room, the Painted Room, as it has always been called, was the first complete neoclassical interior in Europe.

The Spencers entertained constantly and were generous patrons. Spencer House was often used for plays and concerts, and Georgiana grew up in an extraordinarily sophisticated milieu of writers, politicians, and artists. After dinner the guests would sometimes be entertained by a soliloquy delivered by the actor David Garrick or a reading by the writer Laurence Sterne, who dedicated a section of

Tristram Shandy to the Spencers. The house had been built not to attract artists, however, but to consolidate the political prestige and influence of the family. The urban palaces of the nobility encircled the borough of Westminster, where the Houses of Parliament reside, like satellite courts. They were deliberately designed to combine informal politics with a formal social life. A ball might fill the vast public rooms one night, a secret political meeting the next. Many a career began with a witty remark made in a drawing room; many a governmentpolicy emerged out of discussions over dinner. Jobs were discreetly sought, positions gained, and promises of support obtained in return. This was the age of oligarch politics, when the great landowning families enjoyed unchallenged pre-eminence in government. While the Lords sat in the chamber known as the Upper House, or the House of Lords, their younger brothers, sons, and nephews filled up most of the Lower House, known as the House of Commons. There were very few electoral boroughs in Britain which the aristocracy did not own or at least have a controlling interest in. Since the right to vote could only be exercised by a man who owned a property worth at least forty shillings, wealthy families would buy up every house in their local constituency. When that proved impossible there were the usual sort of inducements or threats that the biggest employer in the area could employ to encourage compliance among local voters. Land conferred wealth, wealth conferred power, and power, in eighteenth-century terms, meant access to patronage, from lucrative government sinecures down to the local parish office, worth £20 ($1,980 today) per annum.

Ironically, there was a condition attached to Lord Spencer’s inheritance: by the terms of the will he could be a politician so long as he always retained his independent voice in Parliament. He was never to accept a gov- ernment position or a place in the Cabinet.* He retained great influence because he could use his wealth to support the government, but his political ambitions were thwarted. As a result he had no challenges to draw him out, and little experience of applying himself. He led a life dedicated to pleasure and, in time, the surfeit of ease took its toll. Lord Spencer became diffident and withdrawn. The indefatigable diarist Lady Mary Coke, a distant relation, once heard him speak in Parliament and thought “as much as could be heard was very pretty, but he was extremely frightened and spoke very low.” The Duke of Newcastle awarded him an earldom in 1765 in recognition of his consistent loyalty. But Lord Spencer’s elevation to the peerage failed to prevent him from becoming more self-absorbed with each passing year. His friend Viscount Palmerston reflected sadly: “He seems to be a man whose value few people know. The bright side of his character appears in private and the dark side in public. . . . it is only those who live in intimacy with him who know that he has an understanding and a heart that might do credit to any man.”

Lady Spencer knew her husband could be generous and sensitive. Margaret Georgiana Poyntz, known as Georgiana, met John Spencer in 1754 when she was seventeen, and immediately fell in love with him. “I will own it,” she confided to a friend, “and never deny it that I do love Spencer above all men upon Earth.” He was a handsome man then, with deep-set eyes and thin lips which curled in a cupid’s bow. His daughter inherited from him her unusual height and russet-coloured hair. When Lady Spencer first knew him he loved to parade in the flamboyant fashions of the French aristocracy. At one masquerade he made a striking figure in a blue and gold suit with white leather shoes topped with blue and gold roses.

Georgiana’s mother had delicate cheekbones, auburn hair, and deep brown eyes which looked almost black against her pale complexion. The fashion for arranging the hair away from the face suited her perfectly. It helped to disguise the fact that her eyes bulged slightly, a feature which she passed on to Georgiana. She was intelligent, exceptionally well read, and, unusually for women of her day, she could read and write Greek as well as French and Italian. A portrait painted by Pompeo Batoni in 1764 shows her surrounded by her interests: in one hand she holds a sheaf of music–she was a keen amateur composer–near the other lies a guitar; there are books on the table and in the background the ruins of ancient Rome, referring to her love of all things classical. “She has so decided a character,” remarked Lord Bristol, “that nothing can warp it.”

Her father, Stephen Poyntz, had died when she was thirteen, leaving the family in comfortable but not rich circumstances. He had risen from humble origins–his father was an upholsterer–by making the best of an engaging manner and a brilliant mind. He began his career as a tutor to the children of Viscount Townshend and ended it a Privy Councillor to King George II. Accordingly, he brought up his children to be little courtiers like himself: charming, discreet, and socially adept in all situations. Vice was tolerated so long as it was hidden. “I have known the Poyntzes in the nursery,” Lord Lansdowne remarked contemptuously, “the Bible on the table, the cards in the drawer.”

“Never was such a lover,” remarked the prolific diarist and chronicler of her times Mrs. Delany, who watched young John Spencer ardently court Miss Poyntz during the spring and summer of 1754. The following year, in late spring, the two families, the Poyntzes and the Spencers, made a week-long excursion to Wimbledon Park. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind about the outcome and yet Spencer was in an agony of anticipation throughout the visit. At the last moment, with the carriages waiting to leave, he drew her aside and blushingly produced a diamond and ruby ring. Inside the gold band, in tiny letters, were the words: “MON COEUR EST TOUT À TOI. GARDE LE BIEN POUR MOI.”*

The first years of their married life were happy. The Duke of Queensberry, known as “Old Q,” declared that the Spencers were “really the happiest people I ever saw in the marriage system.” They delighted in each other’s company and were affectionate in public as well as in private. In middle age, Lady Spencer proudly told David Garrick, “I verily believe that we have neither of us for one instant repented our lot from that time to this.” They had “modern” attitudes both in their taste and in their attitude to social mores. Their daughter Harriet recorded an occasion when Lord Spencer took her to see some mummified corpses in a church crypt because “it is foolish and superstitious to be afraid of seeing dead bodies.” Another time he “bid us observe how much persecution encreased [the] zeal for the religion [of the sect] so oppressed, which he said was a lesson against oppression, and for toleration.”

The Spencers were demonstrative and affectionate parents. “I think I have experienced a thousand times,” Lady Spencer mused, “that commendation does much more good than reproof.” She preferred to obtain obedience through indirect methods of persuasion, as this letter to eleven-year-old Georgiana shows: “I would have neither of you go to the Ball on Tuesday, tho’ I think I need not have mentioned this, as I flatter myself you would both chose rather to go with me, than when I am not there. . . .” It was a sentiment typical of an age influenced by the ideas of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose books had helped to popularize the cult of “sensibility.” In some cases the new, softer attitudes ran to ridiculous excesses. The biographer and sexual careerist James Boswell, whose views on children were as tolerant as his attitude towards adultery, complained that his dinner party was ruined when the Countess of Rothes insisted on bringing her two small children, who “played and prattled and suffered nobody to be heard but themselves.”

Georgiana’s education reflected her parents’ idea of a sound upbringing. During the week a succession of experts trooped up and down the grand staircase to the bare schoolroom overlooking the courtyard. There, for most of the day, Georgiana studied a range of subjects, both feminine (deportment and harp-playing) and practical (geography and languages). The aim was to make her polished but not overly educated. The royal drawing-master and miniaturist John Gresse taught her drawing. The composer Thomas Linley, later father-in-law to the playwright Richard Sheridan, gave her singing lessons. The distinguished orientalist Sir William Jones, who was preparing her brother, George, forHarrow, taught her writing. She also learned French, Latin, Italian, dancing, and horsemanship. Everything came easily to her, but what delighted Georgiana’s mother in particular was her quick grasp of etiquette. Lady Spencer’s own upbringing as a courtier’s daughter made her keenly critical of Georgiana’s comportment in public; it was almost the only basis, apart from religion, on which she judged her, praised her, and directed her training.

Lady Spencer’s emphasis on acquiring social skills encouraged the pers former in Georgiana. In quiet moments she would curl up in a window seat in the nursery and compose little poems and stories to be recited after dinner. She loved to put on an “evening” and entertain her family with dramatic playlets featuring heroines in need of rescue. While Georgiana bathed in the limelight, George concentrated on being the dependable, sensible child who could be relied upon to remember instructions. Harriet, despite being the youngest, enjoyed the least attention of all. Perhaps in another family, her obvious sensitivity and intelligence would have marked her out as a special child. But with a precocious and amusing sister and model brother, she had no special talent of her own to attract her parents’ notice. Instead she attached herself to Georgiana, content to worship her and perform the duties of a faithful lieutenant. Even here poor Harriet often had to compete with George. He was proud of Georgiana’s talent and at Harrow would show round the verse letters he had received from her. “By this time there is not an old Dowager in or about Richmond that has not a copy of them; there’s honour for you!” he informed her. On one occasion he imagined the two of them achieving fame by publishing her letters under the title, “An epistle from a young lady of quality abroad to her Brother at School in England.”

Georgiana could think of nothing more delightful than a public exhibition of her writing. Despite being the clear favourite of the family she was anxious and attention-seeking, constantly concerned about disappointing her parents. “Although I can’t write as well as my brother,” she told them plaintively when she was seven, “I love you very much and him just as much.” Adults never failed to be charmed by Georgiana’s lively and perceptive conversation and yet she valued their praise only if it made an impression on her mother and father. Her ability to attract notice pleased Lady Spencer as much as its origins puzzled her: “Without being handsome or having a single good feature in her face,” she remarked to a friend, “[she is] one of the most showy girls I ever saw.” Lady Spencer never understood her daughter’s need for attention or its effect on her development. In later years, when forced to examine her part in Georgiana’s misfortunes, she blamed herself for having been too lenient a parent.

In 1763, when Georgiana was six, the stability she had enjoyed came to an abrupt end when the Spencers embarked on a grand tour. Lord Spencer had trouble with his lungs and his invalid condition made him badtempered. Lady Spencer, worn down by his moods, urged him to rest and heal in the warmer climate of the Continent. Most of their friends were going abroad. Britain had been at war with France for the previous seven years and, although the fighting had largely taken place in outposts–in Canada, India, and the Caribbean–visits across the Channel were severely curtailed. With the advent of peace, travel became possible again and the English aristocracy could indulge in its favourite pastime: visiting “the sights.”

Georgiana accompanied her parents while George and Harriet, both considered too young to undertake such a long journey, stayed behind. The Spencers’ first stop was Spa, in what is now Belgium, in the Ardennes forest. Its natural warm springs and pastoral scenery made it a fashionable watering place among the European nobility, who came to drink the waters and bathe in the artificially constructed pools. But Lady Spencer’s hopes that its gentle atmosphere would soothe her husband’s nerves were disappointed. A friend who stayed with them for a short while described the visit as one of the worst he had ever made: “If you ask me really whether I had a great deal of pleasure in it I must be forced to answer in the negative. Lord S’s unhappy disposition to look always on the worst side of things, and if he does not find a subject for fretting to make one, rendered both himself and his company insensible to much of the satisfaction which the circumstances of our journey might have occasioned us.”

Undaunted, Lady Spencer decided they should try Italy. She wrote to her mother in July and asked her to come out to Spa to look after Georgiana while they were away. She admitted that she was leaving Georgiana behind “with some difficulty,” but she had always placed her role as a wife before that of motherhood. For Georgiana, already missing her siblings, her mother’s sudden and inexplicable abandonment was a profound shock. “Miss Spencer told me today she lov’d me very well but did not like to stay with me without her mama,” her grandmother recorded in her diary. For the next twelve months Georgiana lived in Antwerp with her grandmother, who supervised her education. Believing, perhaps, that her parents had left her behind as a punishment for some unnamed misdeed, Georgiana became acutely self-conscious and anxious to please. She imitated her grandmother’s likes and dislikes, training herself to anticipate the expectations of adults. “We are now 38 at table,” Mrs. Poyntz wrote in June 1764, ten months after Georgiana’s parents had left Spa. “Miss Spencer is adored by all the company, they are astonished to see a child of her age never ask for anything of the dinner or desert but what I give her.”

When her daughter and son-in-law returned Mrs. Poyntz was amazed at the intensity of Georgiana’s reaction: “I never saw a child so overjoy’d, she could hardly speak or eat her dinner.” Lady Spencer immediately noticed that there was something different about her daughter but she decided she liked the change. “I had the happiness of finding my dear Mother and Sweet girl quite well,” she wrote to one of her friends; “the latter is vastly improved.” Although Lady Spencer did not realize it, the improvement was at the cost of Georgiana’s self-confidence. Without the inner resources which normally develop in childhood, she grew up depending far too much on other people. As a child it made her obedient; as an adult it made her susceptible to manipulation.

Three years later, in 1766, a tragedy occurred which had repercussions for the whole family. Lady Spencer had become pregnant with her fourth child and, in the autumn of 1765, gave birth to a daughter named Charlotte. The child symbolized a much needed fresh start after the Spencers’ eighteen-month absence from England, which was perhaps why she engrossed Lady Spencer’s attention just as Georgiana had done nine years before. “She is a sweet little poppet,” she wrote. This time Lady Spencer breastfed the baby herself instead of hiring a wet nurse, and persevered even though it hurt and made her “low.” Georgiana’s notes to her mother when Lady Spencer was in London suggest that she was more than a little jealous of the new arrival. But infant mortality, although improved since the seventeenth century, was still high. Charlotte died shortly after her first birthday.

Lord and Lady Spencer were shattered by the loss. “You know the perhaps uncommon tenderness I have for my children,” Lady Spencer explained to her friend Thea Cowper. Three years later, in 1769, Charlotte was still very much in her heart when she had another daughter, whom they called Louise. But she too died after only a few weeks. After this the Spencers travelled obsessively, sometimes with and sometimes without the children, never spending more than a few months in England at a stretch. Seeking an answer for their “heavy affliction,” they turned to religion for comfort and Lady Spencer began to show the first signs of the religious fanaticism which later overshadowed her life.

At night, however, religion was far from their thoughts as they sought distraction in more worldly pursuits. They set up gaming tables at Spencer House and Althorp and played incessantly with their friends until the small hours. Lady Spencer tried to control herself: “Played at billiards and bowls and cards all evening and a part of the night,” she wrote in her diary. “Enable me O God to persevere in my endeavour to conquer this habit as far as it is a vice,” she prayed on another occasion. The more hours she spent at the gambling table, the more she punished herself with acts of self-denial. By the time Georgiana was old enough to be conscious of her mother’s routine, Lady Spencer had tied herself to a harsh regimen: up at 5:30 every morning, prayers for an hour, the Bible for a further hour, followed by a meager breakfast at nine, and then household duties and good works until dinner. But in her heart she knew that her actions contained more show than feeling. “I know,” she wrote, “that there is a mixture of Vanity and false humility about me that is detestable.” However, knowledge of her faults did not change her ways. Twenty years later a friend complained: “She is toujours Lady Spencer, Vanity and bragging will not leave her, she lugg’d in by the head and shoulders that she had been at Windsor.”

The children were silent witnesses to their parents’ troubled life. Sometimes Georgiana and Harriet would creep downstairs to watch the noisy scenes taking place around the gaming table. “I staid till one hour past twelve, but mama remained till six next morning,” Harriet wrote in her diary. When the children were older they were allowed to participate. Harriet recorded on a trip to Paris: “A man came today to papa to teach him how he might always win at Pharo, and talked of it as a certainty, telling all his rules, and when papa told him he always lost himself, the man assur’d him it was for want of money and patience, for that his secret was infallible. Everybody has given him something to play for them, and papa gave him a louis d’or for my sister and me.”

Georgiana reacted to the loss of Charlotte and Louise by worrying excessively about her two younger siblings. She also became highly sensitive to criticism and the smallest remonstrance produced hysterical screams and protracted crying. Lady Spencer tried many different experiments to calm Georgiana, forcing her to spend hours in prayer and confining her to her room–to little effect.It was in her nature to oversee every aspect of a project, and from this time forward Lady Spencer left nothing in Georgiana’s development to chance. Even her thoughts were subject to scrutiny. “Pray sincerely to God,” Lady Spencer ordered her, “that he would for Jesus Christ’s sake give his assistance without which you must not hope to do anything.”

When she reached adolescence Georgiana’s tendency to over-react became less marked, but not enough to allay her mother’s fear for her future happiness. In November 1769 both George and Harriet were dangerously ill and Lady Spencer confided to a friend that the twelve-year-old Georgiana had shown “upon this as upon every other occasion such a charming sensibility that it is impossible not to be pleased with it, tho when I reflect upon it I assure you it gives me concern as I know by painful experience how much such a disposition will make her suffer hereafter.”

* Misspellings have been corrected only where they intrude on the text.

* Georgiana became Lady Georgiana Spencer at the age of eight when her father, John Spencer, was created the first Earl Spencer in 1765. For the purpose of continuity the Spencers will be referred to as Lord and Lady throughout.

† The usual method for estimating equivalent twentieth-century dollar values is to multiply by 100.

* The Spencers originally came from Warwickshire, where they farmed sheep. They were successful businessmen, and with each generation the family grew a little richer. By 1508 John Spencer had saved enough capital to purchase the 300-acre estate of Althorp. He also acquired a coat of arms and a knighthood from Henry VIII. His descendants were no less diligent, and a hundred years later, when Robert Spencer was having his portrait painted for the saloon, he was at the head of one of the richest farming families in England. King James I, who could never resist an attractive young man, gave him a peerage and a diplomatic post to the court of Duke Frederick of Württemberg. From then on the Spencers left farming to their agents and concentrated on court politics.

* His father, the Hon. John Spencer, was in fact a younger son and, given the law of primogeniture, had always expected to marry his fortune or live in debt. However, his mother was the daughter of the first Duke of Marlborough, and the Marlboroughs had no heir. To prevent the line from dying out the Marlboroughs obtained special dispensation for the title to pass through the female line. John’s older brother Charles became the next Duke. John, meanwhile, became head of the Spencer family and subsequently inherited Althorp. Charles had inherited the title but, significantly, he had no right to the Marlborough fortune until his grandmother Duchess Sarah, the widowed Duchess of Marlborough, died. Except for Blenheim Palace, she could leave the entire estate to whomever she chose. Sarah had strong political beliefs and she was outraged when Charles disobeyed her instruction to oppose the government of the day. In retribution she left Marlborough’s £1 million estate to John, with the sole proviso that neither he nor his son should ever accept a government post.

* My heart is yours. Keep it well.

Copyright © 2008 by Amanda Foreman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.