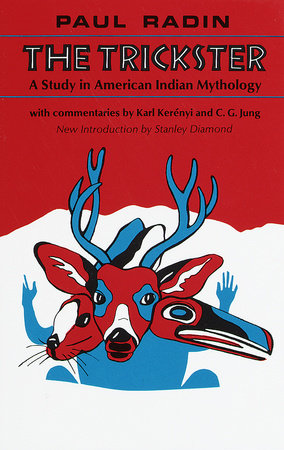

PREFATORY NOTE

Few myths have so wide a distribution as the one, known by the name of

The Trickster, which we are presenting here. For few can we so confidently assert that they belong to the oldest expressions of mankind. Few other myths have persisted with their fundamental content unchanged. The Trickster myth is found in clearly recognizable form among the simplest aboriginal tribes and among the complex. We encounter it among the ancient Greeks, the Chinese, the Japanese, and in the Semitic world. Many of the Trickster’s traits were perpetuated in the figure of the mediaeval jester, and have survived right up to the present day in the Punch-and-Judy plays and in the clown. Although repeatedly combined with other myths and frequently drastically reorganized and reinterpreted, its basic plot seems always to have succeeded in reasserting itself.

Manifestly we are here in the presence of a figure and a theme or themes which have had a special and permanent appeal and an unusual attraction for mankind from the very beginnings of civilization. In what must be regarded as its earliest and most archaic form, as found among the North American Indians, Trickster is at one and the same time creator and destroyer, giver and negator, he who dupes others and who is always duped himself. He wills nothing consciously. At all times he is constrained to behave as he does from impulses over which he has no control. He knows neither good nor evil yet he is responsible for both. He possesses no values, moral or social, is at the mercy of his passions and appetites, yet through his actions all values come into being. But not only he, so our myth tells us, possesses these traits. So, likewise, do the other figures of the plot connected with him: the animals, the various supernatural beings and monsters, and man.

Trickster himself is, not infrequently, identified with specific animals, such as raven, coyote, hare, spider, but these animals are only secondarily to be equated with concrete animals. Basically he possesses no well-defined and fixed form. As he is represented in the version of the Trickster myth we are publishing here, he is primarily an inchoate being of undetermined proportions, a figure foreshadowing the shape of man. In this version he possesses intestines wrapped around his body, and an equally long penis, likewise wrapped around his body with his scrotum on top of it. Yet regarding his specific features we are, significantly enough, told nothing.

Laughter, humour, and irony permeate everything Trickster does. The reaction of the audience in aboriginal societies to both him and his exploits is prevailingly one of laughter tempered by awe. There is no reason for believing this is secondary or a late development. Yet it is difficult to say whether the audience is laughing at him, at the tricks he plays on others, or at the implications his behaviour and activities have for them.

How shall we interpret this amazing figure? Are we dealing here with the workings of the mythopoeic imagination, common to all mankind, which, at a certain period in man’s history, give us his picture of the world and of himself? Is this a

speculum mentis wherein is depicted man’s struggle with himself and with a world into which he had been thrust without his volition and consent? Is this the answer, or the adumbration of an answer, to questions forced upon him, consciously or unconsciously, since his appearance on earth?

On the basis of the very extensive data which we have today from aboriginal tribes it is not only a reasonable but, indeed, almost a verifiable hypothesis that we are here actually in the presence of such an archaic

speculum mentis. Our problem is this basically a psychological one. In fact, only if we view it as primarily such, as an attempt by man to solve his problems inward and outward, does the figure of Trickster become intelligible and meaningful. But we cannot properly and fully understand the nature of these problems or the manner in which they have been formulated in the various Trickster myths unless we study these myths in their specific cultural environments and in their historical settings.

The following paper is the presentation of one such Trickster myth, that found among the Siouan-speaking Winnebago of central Wisconsin and eastern Nebraska. To see it in its proper perspective I have added, in Part Two, the Winnebago Hare myth in full and summaries of the Assiniboine and Tlingit Trickster myths.

—Paul Radin

Lugano, 1956

Copyright © 1987 by Paul Radin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.