FOREWORD

ANNA QUINDLEN

Any columnist who makes sweeping generalizations is looking for trouble, but I once did just that in an essay I wrote for

Newsweek. “Teaching’s the toughest job there is,” I said flatly, and the mail poured in. Nursing is tough. Assembly line work is tough. Child rearing is tough. There were even a few letters with some of those old canards about the carefree teacher’s life: work hours that end at 3 p.m., summers at the beach.

I imagine that the people who believe that’s how teachers work don’t actually know anyone who does the job–if they did, they would know that classes may end at 3 p.m., but lesson planning and test correcting go on far into the night, while summers are often reserved for second jobs, which pay the bills. But I’m lucky enough to know lots of teachers, and that’s why I stuck by my statement. More important, I’ve taught a class or two from time to time, and the degree of concentration and engagement required–or the degree of hell that broke loose if my concentration and engagement flagged–made me realize that I just wasn’t up to the task. It was too hard.

But if hard was all it was, no one would ever go into the profession, much less the uncommonly intelligent people who, over the years, taught me everything from long division to iambic pentameter. I don’t remember much at this point in my life, but I remember the names of most of the teachers I’ve had during my educational career, and some of them I honor in my heart almost every day because they made me who I am, as a reader, a thinker, and a writer.

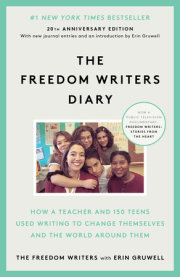

So when I first read about Erin Gruwell and the Freedom Writers, it came as no surprise to me to discover that the truth about teaching was that it was sometimes a grueling job with near- miraculous rewards, for students and for teachers alike. In Erin’s first, internationally known book,

The Freedom Writers Diary, you saw this mainly through the eyes of her high school students, young men and women living with combative families, absent parents, gang warfare, teenage pregnancies, and drug abuse. Above all, they lived with the understanding that no one expected them to do anything–not just anything great, but anything at all. They’d been given up on by just about everyone before they even showed up in class.

Except for Ms. G, as they called her, who was too inexperienced and naïve to get with the surrender or the cynicism program. Her account of assigning her students to write candidly about their own lives and thereby engaging them in the educational process, of how many of them went on to college and to leadership roles in their communities, is a stand-up-and-cheer story. That’s why it was turned into a movie, and why Erin’s model has now been replicated in many other schools.

That first book contained the stripped-bare writings of those students, but in this one, it’s the teachers’ turn to give the rest of us a window into how difficult their job can be. In a way I never could, they answer the naysayers who question the rigor of their jobs. Here are the real rhythms of a good teacher’s life, not bounded by June and September, or eight and three, but boundless because of the boundless needs of young people today and the dedication of those who work with them. These are teachers who attend parole hearings and face adolescents waving weapons, who teach students they know are high or drunk or screaming inside for someone to notice their pain. “Sitting at the funeral of a high school student for the third time in less than a year” is how one teacher begins an entry. There are knives and fists, and then there is the all-too- familiar gaggle of girls who are guilty of “a drive-by with words,” trafficking in the gossip, innuendo, and nastiness that have been part of high school forever. One teacher recalls a reserved and friendless young woman with great academic potential and a wealthy family, and the evening the maid found her “hanging, as silent as the clothing beside her, in the closet.” Another gets a letter from a former student with a return address in a state prison, with this plea: “I know you’re busy but I would be very grateful if you would write to me.”

Yet despite so many difficulties, these are also teachers who weep when budget cuts mean they lose their jobs, teachers who quit and are horrified at what they’ve done and then “unquit,” as one describes it. Some of them have faced the same problems of racial and ethnic prejudice or family conflict as their students, and see their own triumphs mirrored in those of the young people they teach and, often, mentor. One, hilariously, writes of how she is “undateable” because of the demands of her work: “I’m going to have a doozy of a time finding someone willing to welcome me and my 120 children into his life.”

Teachers had an easier time when I was in school, I suspect. Or maybe back then the kinds of problems and crises that confront today’s students existed but were muffled by silence and ignorance. Certainly I was never in a classroom where a student handed over his knife to the teacher. I never had a classmate who was homeless, or in foster care, or obviously pregnant.

And yet many of the teachers here speak my language: of pen pals, class trips, missed assignments–and, above all, of that adult at the front of the room who gives you a sense of your own possibilities. “Isn’t that the job of every teacher,” one of them writes, “to make every student feel welcome, to make every student feel she or he belongs, and to give every student a voice to be heard!”

And so I stick with my blanket statement: It’s the toughest job there is, and maybe the most satisfying, too. There are lives lost in this book, and there are lives saved, too, if salvation means a young man or woman begins to feel deserving of a place on the planet. “Everyone knows I’m gonna fail,” says one boy, and then he doesn’t. What could be more soul- satisfying? These are the most influential professionals most of us will ever meet. The effects of their work will last forever. Each one here has a story to tell, each different, but if there is one sentiment, one sentence, that appears over and over again, it is this simple declaration: I am a teacher. They say it with dedication and pride, and well they should. On behalf of all students–current, former, and those to come–let me echo that with a sentiment of my own: Thank you for what you do.

Copyright © 2009 by The Freedom Writers. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.