Part One

Chapter 1

The Stanford Entertainment

The mansion in San Francisco had collapsed with the earthquake in 1906 and burned to nothing a day later in the fires. I walked up the face of Nob Hill to look at the place where it used to stand. Could there be a tiny remnant of this temple of money? The hill had been known as California Hill until Leland Stanford and family moved there in 1876, followed by their preposterously rich friends. After that it was Nob Hill. Stanford and the other nabobs (a word borrowed from Mughal India, trimmed in America to “nobs”) built houses that showed their money and looked with a possessive gaze at the city below. The day after the earthquake the fire came, on a Thursday morning in April, and the two disasters took down all the big houses but one.

At the top of Nob Hill today are apartment buildings, hotels, a little park. The place that survived, the last sign of the sovereigns who had set themselves up on these blocks, was the Flood house. James Flood, a mining multimillionaire, was one of the men who exploited the Comstock Lode, a thick vein of silver in Nevada that ended up in most coins. The fire had somehow wrapped around and missed his house. When the silver man died, the Flood mansion went into the hands of the Pacific-Union Club, which seems fitting—a men’s club whose members dote on money, the way the nabobs did. I looked at the Flood house, a megalith in brown stucco, and imagined it in its original setting, amid a colony of American palaces. The first and most ostentatious of them, the Stanford house, used to stand a block to the east, at California and Powell Streets. An eight-story hotel now occupied that site, planted over the ruins. Only the granite wall that used to frame the house remained.

Mark Twain’s novel The Gilded Age gave its name to the late nineteenth century, a time of monopoly with its high tide of corruption and greed. Nob Hill was one of the age’s capitals, and whatever went on here took shape in a Brobdingnagian scale. But one episode of those years, as far as I can see, has been overlooked. It could be said that the world of visual media got under way on this hill, amid the new money of California, in the late 1800s. It happened one night at a party, at which the entertainment was a photographer called Edward Muybridge.

January 16, 1880

California and Powell Streets, San Francisco

It was the night pictures began to move. Just what it was that happened that night could not be accurately described for many years. It would not be comprehensible until the movie theaters had spread and the television stations were built, or maybe even until screens appeared in most rooms and people carried them in their hands. That winter night in San Francisco pictures jumped into motion, someone captured time and played it back. A newspaperman noticed that something unusual had happened, although he did not say anything about time. He noticed only that whatever it was that happened had taken place in the home of the best-known citizen of the state of California; he noticed these facts but missed the main event. The newspaperman pointed out that a photographer of angular shape named Edward Muybridge and his new machine had been the reason for the gathering, but he did not describe what Muybridge had done. Thanks to the paper (and notwithstanding the reporter’s oversights), we know who was there, in the house. We know who came around to the stupendous mansion where Muybridge assembled his mechanism and put it in motion and carried it through its initial performance.

The event with the photographer took place in the home of an abnormally rich family. It was the end of the week. The family stayed in for the evening and invited some friends for a party and a show.

Their brown, stuccoed palazzo occupied the best site on California Hill, looking out to the flickering lights on San Francisco Bay and down at the streets of the rolling city. From a block away—and you had to get that far back to see the whole thing—the house looked to be a chunky, dark mass, Italianate in style. The owners of the house wanted it to exceed, if possible, the pomp of the European palaces, and to achieve this they had hired the New York design firm Pottier & Stymus, which had a record of extravagance, to ornament every square yard of its interior. When the decorators were finished, the place had a magnitude and pretense that no one in California had previously seen. Without rival, it was the most talked-up house west of the Mississippi.

The Stanford family lived here, just three people, a mother and father and their eleven-year-old son. The Stanfords employed about twelve servants, half of whom lived in the brown house and some of whom traveled with the family to serve them at their horse farm south of the city. Newspapers were soaked with ink about the Stanfords’ outsized lives. The San Francisco Daily Call labeled tonight’s event “The Stanford Entertainment,” and from those three words everyone knew where and for whom the photographer Edward Muybridge was doing whatever it was he did with his picture machine.

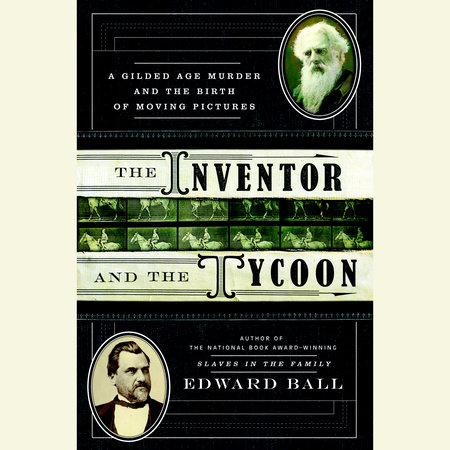

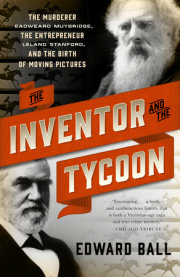

This year he was Edward Muybridge, but the spelling of his name would soon change, as it had done on four previous occasions. Every few years, the photographer would move a vowel or switch a couple of consonants. He used to be Edward Muygridge, and before that, Edward Muggeridge. For a few years he used the professional name “Helios,” the single moniker of an artist, borrowed in this case from the Greek god of the sun.

Along with his name, his working life had already passed through several metamorphoses. During his twenties Muybridge had been a book and print salesman for a London publisher; he sold dictionaries and encyclopedias and art books, engravings, and lithographs. In his thirties he tried to make a living as an inventor but failed when buyers showed indifference to his patents. After that, he put on the top hat of a capitalist: he started a mining company, and then an investment firm. Both ended badly. At age thirty-seven, he invented himself for the last time, as an artist: he became a photographer. He had followed a wandering path and only came to a single road as a middle-aged man. The choice of photography, at last, seemed to him to vindicate all the disappointments and failures that had gone before.

Edward Muybridge wore a beard down to the middle of his chest, a gray weave with a dark residue. Occasionally he might have combed it. The hair on his head was white, swirling at the ears, tossed up from his brow. His eyes were sharp blue. The crinkly beard and flowing hair made him look antique, wizardlike. One newspaper said that Muybridge looked “at least ten years older” than his natural age, which was forty-nine: a man in midlife wearing a mask of seniority.

After twelve years with the camera, he was the best-known photographer in San Francisco. Part of his renown came from his pictures, notably the ones he had taken in Yosemite Valley. The naturalist John Muir had explored and written about the seven-mile-long chasm in upper California, an extravagance of cliffs and depths and vistas. A photographer called Carleton Watkins had been one of the first to descend into Yosemite’s hollows and come back with pictures. But Muybridge’s photographs of the valley’s flagrant rock faces and bridal-veil waterfalls had exceeded those of Watkins and helped to make Yosemite a part of national lore. The landscape of Yosemite, its wildness and excess, which Muybridge framed and made mythic, had come to represent the West to people in the eastern states.

Yosemite was part of Muybridge, but other parts of him were urban. Three years earlier he had made a panorama of San Francisco in photographs, the city in 360 degrees. To shoot it he had stood on the turret of the Mark Hopkins house, another mansion farther up the hill from the Stanford place. Muybridge had cranked the camera around on his tripod, measuring and panning, foot by foot, until the whole city went under the lens. He had given Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane, the biggest version of the panorama, an unrolling carpet of a picture, seventeen feet long and two feet high—an expensive thank-you gift for years of assignments and friendship.

The photographer who tramped the wilderness and scaled city summits had a thin, vigorous body. The same witness who called him “old” also wrote that Muybridge possessed the jauntiness of a twenty-five-year-old man. People knew his athleticism. He was the man who skipped down flights of stairs, the agile camera operator most conspicuous around San Francisco, a blur seen in continual movement from the Golden Gate to San Jose. The tripod went up—it must be Muybridge again—and it came down.

Edward Muybridge had another stroke of renown, outside of his work, which was the fame of his crime. Wherever he went, it followed the photographer. He was a murderer, and the aura of his violence lingered, stirring an atmosphere as palpable as his acclaim as an artist. Muybridge’s crime had been reported throughout the United States, so strange were its details, so fascinating was its passion to so many people. The photographer had a reasonable claim to be the one citizen who pulled behind him the largest cloud of dark gossip in the state of California. Of course he pretended as though the talk about him did not buzz incessantly, that he was merely a member of San Francisco’s small, vivid cultural establishment. Perhaps he had no other choice but to pretend. Certainly this pose worked more to his advantage than fully inhabiting the role of a killer.

Tonight Muybridge stood at a table in the middle of a giant room. In the Stanford mansion, the rooms had names. This one, in all probability, was the Pompeian Room, the showiest room, which the family used to entertain. About forty feet square, it had four walls of murals that replicated frescoes found in houses uncovered beneath the volcanic dirt at Pompeii. The Stanfords had paid Pottier & Stymus, the decorators, to create a showplace of replica history in their house. In the Pompeian Room they had placed gilded chairs and marble-topped tables with slender legs to make a pastiche of ancient Rome, and life-size marble nymphs to stand guard.

If not here, Muybridge may have stood in the Music and Art Room, a gallery twenty yards long whose wine-red walls were hung with fifty-some landscapes and portraits, and whose ceiling was painted with medallions depicting the faces of Rubens, Van Dyck, Beethoven, Mozart, Raphael, and Michelangelo. “Few palaces of Europe excel this house,” said one newswriter, who may not have been to Europe but who knew the fantasies of Americans who looked up to the Old World.

Or he could have been in one of the other downstairs parlors, or in the library, the ballroom, or the aviary. Huge mantelpieces and elaborate rosewood fittings dominated each of them, and a grove of furnishing spread to the edges in leather, silk, brocade, or velvet. Wherever Muybridge was, he had to clear away the crush of decor and work around chandeliers heavy as cannon that dangled just above the head, because he needed a straight thirty feet for what he had to accomplish. Muybridge made pictures that were very different from the imagery that decorated the walls, ceilings, and floors of the Stanford mansion. His pictures were not massive, like most of the fixtures, and they were not imitations of art found in Europe. They were evanescent and thin, they were pictures flung on air.

A scattering of guests arrived in twos and threes, with buttons on bulges, lace on bosoms. Some were politicians, like the newly elected governor of California, George Perkins, and Reuben Fenton, U.S. senator from New York and former governor. Behind the lawmakers came a phalanx of rich people, a few of them as rich as their hosts, the Stanfords. In this group were the neighbors, Charles Crocker and his wife, Mary Ann Deming, who lived two blocks away in a brown house only a little less grand than the Stanfords’ palazzo. There was also a young woman, Jennie Flood, an heiress in the new California manner. She came with her father, James Flood, a silver miner who had gotten rich on specie metal from Nevada and built a supreme and impressive house around the corner, at California and Mason Streets. Lesser elites and their spouses filled out the invitation list—a judge here, a doctor there.

Servants brought in drink, gaslight drank the air. The woman of the house, Mrs. Jane Stanford, presented herself, tall, ample, and bejeweled. Jane Stanford cultivated a gothic look. She liked to drape herself in crimson velvet, with pools of hem and long trains behind, old lace circling her neck. She was sure to be wearing an arm’s length of opals or a parure of diamonds consisting of necklace, bracelets, and earrings.

The night promised a pageant of some kind, but two men already radiated something of the theater. Leland Stanford and Edward Muybridge were the best-known men at the party—Stanford for his money, Muybridge for his pictures (as well as the other thing), and together they inspired most of the hushed chatter. They had known each other for almost ten years and had spent a lot of that time talking and wondering about a single subject: the gait of horses. A narrow topic, yes, but one on the mind of many in the year 1880. Everyone knew that Stanford was horse-mad, and that he and Muybridge had formed a bond over horses. It was Stanford’s belief that during a gallop, horses at some point in their stride lift all four hooves off the ground, that in effect, they become airborne. No one knew, really—the legs of a horse moved too fast to tell with the eye. Stanford had asked Muybridge to solve his problem, to prove or disprove his hypothesis, which horse people referred to as the theory of “unsupported transit.”

Some of the talk that Stanford aroused would not have flattered him. At least some of the guests at the party, perhaps the politicians and the more middle-class group, inevitably regarded their hosts with ambivalence—envy would not be too strong a word, and maybe a touch of fear. Almost twenty years before, Leland Stanford and several others had founded the Central Pacific Railroad, with Stanford in the role of company president. The firm, using big government subsidies, and the sweat of perhaps twenty thousand Chinese immigrants, had built the western half of the transcontinental line, the 850-mile track over the Sierra Mountains that linked California to the eastern states. In the early years of the Central Pacific, Stanford had been an object of fealty. Newspaper accounts painted him as a great benefactor of California: he brought work and wealth and even glory to the West, his admirers said, justifying the stage name of California, the Golden State.

Copyright © 2013 by Edward Ball. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.