SIGNATURE

I GAZE OUT A WINDOW, a clear, puck-shaped box in my hand. Life fills my view: fescue and clover spreading out across the yard, rose of Sharon holding out leaves to catch sunlight and flowers to lure bumblebees. An orange cat lurks under a lilac bush, gazing up at an oblivious goldfinch. Snowy egrets and seagulls fly overhead. Stinkhorns and toadstools rudely surprise. All of these things have something in common with one another, something not found in rocks or rivers, in tugboats or thumbtacks. They live.

The fact that they live may be obvious, but what it means for them to be alive is not. How do all of the molecules in a snowy egret work together to keep it alive? That's a good question, made all the better by the fact that scientists have decoded only a few snips of snowy egret DNA. Most other species on Earth are equally mysterious. We don't even know all that much about ourselves. We can now read the entire human genome, all 3.5 billion base pairs of DNA in which the recipe for

Homo sapiens is written. Within this genetic tome, scientists have identified about 18,000 genes, each of which encodes proteins that build our bodies. And yet scientists have no idea what a third of those genes are for and only a faint understanding of most of the others. Our ignorance actually reaches far beyond protein-coding genes. They take up only about 2 percent of the human genome. The other 98 percent of our DNA is a barely explored wilderness.

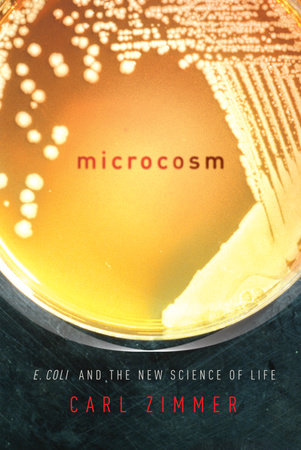

Only a few species on the entire planet are exceptions to this rule. The biggest exception lives in the plastic box in my hand. The box-a petri dish-looks lifeless compared with the biological riot outside my window. A few beads of water cling to the underside of the lid. On the bottom is a layer of agar, a firm gray goo made from dead algae and infused with sugar and other compounds. On top of the agar lies a trail of pale gold spots, a pointillistic flourish. Each of those spots is made up of millions of bacteria. They belong to a species that scientists have studied intensely for a century, that they understand better than almost any other species on the planet. I've made this species my guide-an oracle that can speak of the difference between life and lifeless matter, of the rules that govern all living things-bacteria, snowy egret, and curious human. I turn over the dish. On the bottom is a piece of tape labeled "E. coli K-12 (P1 strain)."

I got my dish of

Escherichia coli on a visit to Osborne Memorial Laboratories, a fortress of a building on the campus of Yale University. On the third floor is a laboratory filled with nose-turning incubators and murky flasks. A graduate student named Nadia Morales put on purple gloves and set two petri dishes on a lab bench. One was sterile, and the other contained a cloudy mush rich with

E. coli. She picked up a loop-a curled wire on a plastic handle-and stuck it in the flame of a Bunsen burner. The loop glowed orange. She moved it away from the flame, and after it cooled down she dipped it into the mush. Opening the empty dish, she smeared a dollop across the sterile agar as if she were signing it. Morales snapped the lid on the second dish and taped it shut.

"You'll probably start seeing colonies tomorrow," she said, handing it to me. "In a few days it will get stinky."

It was as if Morales had given me the philosopher's stone. The lifeless agar in my petri dish began to rage with new chemistry. Old molecules snapped apart and were forged together into new ones. Oxygen molecules disappeared from the air in the dish, and carbon dioxide and beads of water were created. Life had taken hold. If I had microscopes for eyes, I could have watched the hundreds of

E. coli Morales had given me as they wandered, fed, and grew. Each one is shaped like a microscopic submarine, enshrouded by fatty, sugary membranes. It trails propeller-like tails that spin hundreds of times a second. It is packed with tens of millions of molecules, jostling and cooperating to make the microbe grow. Once it grows long enough, it splits cleanly in two. Splitting again and again, it gives rise to a miniature dynasty. When these dynasties grow large enough, they become visible as golden spots. And together the spots reveal the path of Morales's living signature.

E. coli may seem like an odd choice as a guide to life if the only place you've heard about it is in news reports of food poisoning. There are certainly some deadly strains in its ranks. But most

E. coli are harmless. Billions of them live peacefully in my intestines, billions more in yours, and many others in just about every warm-blooded animal on Earth. They live in rivers and lakes, forests and backyards. And they also live in thousands of laboratories, nurtured in yeasty flasks and smeared across petri dishes.

In the early twentieth century, scientists began to study harmless strains of

E. coli to understand the nature of life. Some of them marched to Stockholm in the late 1900s to pick up Nobel Prizes for their work. Later generations of scientists probed even further into

E. coli's existence, carefully studying most of its 4,000-odd genes and discovering more rules to life. In

E. coli, we can begin to see how genes must work together to sustain life, how life can defy the universe's penchant for disorder and chaos. As a single-celled microbe,

E. coli may not seem to have much in common with a complicated species like our own. But scientists keep finding more parallels between its life and ours. Like us,

E. coli must live alongside other members of its species, in cooperation, conflict, and conversation. And like us,

E. coli is the product of evolution. Scientists can now observe

E. coli as it evolves, mutation by mutation. And in

E. coli, scientists can see an ancient history we also share, a history that includes the origin of complex features in cells, the common ancestor of all living things, a world before DNA.

E. coli can not only tell us about our own deep history but can also reveal things about the evolutionary pressures that shape some of the most important features of our existence today, from altruism to death.

Through

E. coli we can see the history of life, and we can see its future as well. In the 1970s, scientists first began to engineer living things, and the things they chose were

E. coli. Today they are manipulating E. coli in even more drastic ways, stretching the boundaries of what we call life. With the knowledge gained from

E. coli, genetic engineers now transform corn, pigs, and fish. It may not be long before they set to work on humans.

E. coli led the way.

I hold the petri dish up to the window. I can see the trees and flowers through its agar gauze. Each spot of the golden signature refracts their image. I look at life through a lens made of

E. coli.

"LUXURIOUS GROWTH"ESCHERICHIA COLI HAS LURKED WITHIN our ancestors for millions of years, before our ancestors were even human. It was not until 1885 that our species was formally introduced to its lodger. A German pediatrician named Theodor Escherich was isolating bacteria from the diapers of healthy babies when he noticed a rod-shaped microbe that could produce, in his words, a "massive, luxurious growth." It thrived on all manner of food-milk, potatoes, blood. Working at the dawn of modern biology, Escherich could say little more about his new microbe. What took place within

E. coli-the transformation of milk, potatoes, or blood into living matter-was mostly a mystery in the 1880s. Organisms were like biological furnaces, scientists agreed, burning food as fuel and creating heat, waste, and organic molecules. But they debated whether this transformation required a mysterious vital spark or was just a variation on the chemistry they could carry out themselves in their laboratories.

Bacteria were particularly mysterious in Escherich's day. They seemed fundamentally different from animals and other forms of multicellular life. A human cell, for example, is thousands of times larger than

E. coli. It has a complicated inner geography dominated by a large sac known as the nucleus, inside of which are giant structures called chromosomes. In bacteria, on the other hand, scientists could find no nucleus, nor much of anything else. Bacteria seemed like tiny, featureless bags of goo that hovered at the boundary of life and nonlife.

Escherich, a forward-thinking pediatrician, accepted a radical new theory about bacteria: far from being passive goo, they infected people and caused diseases. As a pediatrician, Escherich was most concerned with diarrhea, which he called "this most murderous of all intestinal disease." A horrifying number of infants died of diarrhea in nineteenth-century Germany, and doctors did not understand why. Escherich was convinced-rightly-that bacteria were killing the babies. It would be no simple matter to find those pathogens, however, because the guts of the healthiest babies were rife with bacteria. Escherich would have to sort out the harmless species of microbes before he could recognize the killers.

"It would appear to be a pointless and doubtful exercise to examine and disentangle the apparently randomly appearing bacteria," he wrote. But he tried anyway, and in that survey he came across a harmless-seeming resident we now call

E. coli. Escherich published a brief description of

E. coli in a German medical journal, along with a little group portrait of rod-shaped microbes. His discovery earned no headlines. It was not etched on his gravestone when he died, in 1911.

E. coli was merely one of a rapidly growing list of species of bacteria that scientists were discovering. Yet it would become Escherich's great legacy to science.

Its massive luxurious growth would bloom in laboratories around the world. Scientists would run thousands of experiments to understand its growth-and thereby to understand the fundamental workings of life. Other species would also do their part in the rise of modern biology. Flies, watercress, vinegar worms, and bread mold all had their secrets to share. But the story of

E. coli and the story of modern biology are extraordinarily intertwined. When scientists were at loggerheads over some basic question of life-what are genes made of? do all living things have genes?-it was often

E. coli that served as the expert witness. By understanding how

E. coli produced its luxurious growth-how it survived, fed, and reproduced-biologists went a great way toward understanding the workings of life itself. In 1969, when the biologist Max Delbrück accepted a Nobel Prize for his work on

E. coli and its viruses, he declared, "We may say in plain words, 'This riddle of life has been solved.' "

THE UNITY OF LIFE

Escherich originally dubbed his bacteria

Bacterium coli communis: a common bacterium of the colon. In 1918, seven years after Escherich's death, scientists renamed it in his honor. By the time it got a new name, it had taken on a new life. Microbiologists were beginning to rear it by the billions in their laboratories.

In the early 1900s, many scientists were pulling cells apart to see what they were made of, to figure out how they turned raw material into living matter. Some scientists studied cells from cow muscles, others sperm from salmon. Many studied bacteria, including

E. coli. In all of the living things they dissected, scientists discovered the same basic collection of molecules. They focused much of their attention on proteins. Some proteins give life its structure-the collagen in skin, the keratin in a horse's hoof. Other proteins, known as enzymes, usher other molecules into chemical reactions. Some enzymes split atoms off molecules, and others weld molecules together.

Proteins come in a maddening diversity of complicated shapes, but scientists discovered that they also share an underlying unity. Whether from humans or bacteria, proteins are all made from the same building blocks: twenty small molecules known as amino acids. And these proteins work in bacteria much as they do in humans. Scientists were surprised to find that the same series of enzymes often carry out the same chemical reactions in every species.

"From the elephant to butyric acid bacterium-it is all the same!" the Dutch biochemist Albert Jan Kluyver declared in 1926.

The biochemistry of life might be the same, but for scientists in the early 1900s, huge differences seemed to remain. The biggest of all was heredity. In the early 1900s, geneticists began to uncover the laws by which animals, plants, and fungi pass down their genes to their offspring. But bacteria such as

E. coli didn't seem to play by the same rules. They did not even seem to have genes at all.

Much of what geneticists knew about heredity came from a laboratory filled with flies and rotten bananas. Thomas Hunt Morgan, a biologist at Columbia University, bred the fly

Drosophila melanogaster to see how the traits of parents are passed on to their offspring. Morgan called the factors that control the traits genes, although he had no idea what genes actually were. He did know that mothers and fathers both contributed copies of genes to their offspring and that sometimes a gene could fail to produce a trait in one generation only to make it in the next. He could breed a red-eyed fly with a white-eyed one and get a new generation of flies with only red eyes. But if he bred those hybrid flies with each other, the eyes of some of the grandchildren were white.

Morgan and his students searched for molecules in the cells of

Drosophila that might have something to do with genes. They settled on the fly's chromosomes, those strange structures inside the nucleus. When chromosomes are given a special stain, they look like crumpled striped socks. The stripes on

Drosophila chromosomes, Morgan and his students discovered, are as distinctive as bar codes. Chromosomes mostly come in pairs, one inherited from each parent. And by comparing their stripes, Morgan and his students demonstrated that chromosomes can change from one generation to the next. As a fly's sex cells develop, each pair of chromosomes embrace and swap segments. The segments a fly inherited determined which genes it carried.

There was something almost mathematically abstract about these findings. George Beadle, one of Morgan's graduate students, decided to bring genes down to earth by figuring out exactly how they controlled a single trait, such as eye color. Working with the biochemist Edward Tatum, Beadle tried to trace cause and effect from a fly's genes to the molecules that make up the pigment in its eyes. But that experiment soon proved miserably complex. Beadle and Tatum abandoned flies for a simpler species: the bread mold

Neurospora crassa.

Bread mold may not have obvious traits such as eyes and wings, but it does produce many enzymes, some of which build amino acids. To see how the mold's genes control those enzymes, Beadle and Tatum bombarded it with X-rays. They knew that when fly larvae are exposed to X-rays, the radiation mutates some of their genes. The mutations produce new traits-extra wings or a different eye color-which mutant flies can pass down to their offspring.

Copyright © 2008 by Carl Zimmer. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.