|

David Lipsky on David Foster Wallace Highlights for LibraryThing’s State of the Thing April newsletter |

|

If you’ve never read DFW before, here’s a list of the highlights—and if you have opened one of his books, you probably already know it’s almost all highlights. David Wallace had the rarest gift for a writer. He made you feel smarter while and after you read him. He’s like a mental vitamin pill. And it’s not the kind of brightness that makes you feel stubby, the brightness of the kid who keeps raising a hand in class. It’s a brilliance that welcomes you, that says, “I know you noticed this, come over here and be smart with me.” Wallace was aware of this, too. He said, “What writers have is a license and also the freedom to sit—to sit, clench their fists, and make themselves be excruciatingly aware of the stuff that we’re mostly aware of only on a certain level. And if the writer does his job right, what he basically does is remind the reader of how smart the reader is. Is to wake the reader up to stuff that the reader’s been aware of all the time.” David Wallace’s work is a wake-up pill, a slug of coffee; that’s what the following stories, essays and novels stories are like. I hope you find this list useful.

The Broom of the System DFW’s first novel, written his last year in college, published when he was 24. David had his own doubts about it. He said it “showed some talent” but was in lots of ways not a project he felt entirely comfortable with. “The philosophy thesis I was gonna do looked really hard and I was really scared about it, and I thought I would do this jaunty thing. Kind of like a side—I figured it would be like a hundred- page thing. And Broom of the System, the first draft was seven-hundred pages long. It was written in like five months.”

Girl With Curious Hair His first collection of stories. “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” is very long and famous and lots of fun if you’re a DFW fan, but maybe not an ideal place to begin. “Little Expressionless Animals” is about the TV show Jeopardy! scrambling to topple an unbeatable contestant; “My Appearance” is about an actress who’s so nervous filling her first guest-chair on the David Letterman Show that she has her husband feed her jokes via a hidden earpiece. (The film critic Pauline Kael, a hero of DFW’s, said this was a story she especially admired.) There’s also the title story, which is good nasty fun that absolutely brings back the punk era. And “Here and There” is really very beautiful. Plus, it’s a good writing program revenge story. In David’s first year at grad school, his professors threatened he might be kicked out. He turned in “Here and There,” his professor hated it—and then it got picked by the O. Henry Prize Stories collection as one of the best of its year. “And it was all I could do not to, you know, send him the jacket of the book. I mean, to do something really like that, because he had hurt my feelings.”

Extra Credit Point: “Here and There” is a campus romance story, which in general David seemed to feel was a bad bet. “Never—don't go there. The great dread of creative writing teachers: ‘Their eyes met over the keg.’”

Infinite Jest An extraordinary book, his second novel. When it came out in 1996, it was like a readers’ micro-climate; every conversation about books took place a little under it, everywhere you went, people brought up the book. It is, of course, a commitment; it’s a first date you marry on. If you’d like to date it for a little while first, you could start on p. 809 (Kindle and iPad users, the first line is “The ceiling was breathing”), and read the heroic section about Don Gately in the hospital, then follow it through a wonderfully funny and harrowing underworld story all the way to the end. You’d be cheating yourself of what is an amazing reading experience, but it might make it easier to then go back and start the whole thing. If anyone is interested, you could email me through Librarything, and I could send a summary that would let you read those last 170 pps while staying up-to-date on what’s happened in the book. The section is a wonderful introduction to what makes this novel so extraordinary; a nearly unimaginably full book. When it came out, the Walter Kirn said, “The competition has been obliterated. It's as though Paul Bunyan had joined the NFL, or Wittgenstein had gone on Jeopardy! The novel is that colossally disruptive. And that spectacularly good.”

A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again The best place to start with DFW. It’s warm, brilliant, funny, kind: the essays here are endlessly charming—they’re the best friend you could ever have, noticing everything, whispering jokes, sweeping you past what’s irritating or boring or awful in humane style. The best piece is the title essay, about a week David spent on a cruise ship; for me, it’s the single most fun piece of writing in the last 15 years. (When David’s editor at Harper’s received the piece, he said, “It was very clear to us that we had pure cocaine on our hands.” The writing is that irresistible.) The collection shows every kind of strength: a lot of the pieces are what David calls “experiential postcards,” but what they also demonstrate is what in tennis is called a complete game. Every type of stroke, every kind of wit, every sort of follow-through. Aside from the title story, I’d recommend the piece actually about tennis (“Tennis Player Michael Joyce…”), the piece about filmmaker David Lynch (“David Lynch Keeps His Head”; great film crew personnel line, “the sort of sloppily pretty tech-savvy young woman you can just tell smokes pot and owns a dog”), and, especially, the piece about attending the Illinois State Fair (“Getting Away From Already Pretty Much Being Away From It All”). The last one is funny about hazardous baton-twirling (“a dad standing up near the stands’ top takes a tomahawking baton directly to the groin and falls forward onto somebody eating a Funnel Cake”), cows, and has the best list of t-shirts I’ve ever read. (“Some presume a weird kind of aggressive relation between the shirt’s wearer and its reader—‘We’d Get Along Better…If You Were A Beer.”) If you’re new to Wallace, these four essays are an ideal handshake.

Extra Credit Point 2: David described these pieces as a chance to ride along inside his head. “It’s basically, you know, welcome to my mind for twenty pages. See through my eyes, here’s pretty much all the French curls and crazy circles. And the trick about that stuff is to have it be honest, but also have it be a lot more interesting. I mean most of our thoughts aren’t all that interesting. They’re mostly just confused.”

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men The writer Zadie Smith did a wonderful piece about this book; it’s the last essay in her 2009 Changing My Mind. She recommends some slightly different stories than I’m about to—I really recommend both her collection and that piece. She calls Wallace’s book “a gift.” Wallace was her favorite living writer.

This collection of stories is incredibly good. Highlights are “The Depressed Person” (the best story on depression I know), “Octet” (a terrifically funny piece about moral dilemmas, designed as a pop quiz; the best is about a researcher who invents an instant and inexpensive cure for depression, then finds his home address leaked and his lawn thronged by gratitude—the pharmacologist is “unable to leave the house and already down to the most unappetizing canned food from the very back of his pantry”), “Adult World”, and two of the “Brief Interviews.” The first, “Brief Interview #42, Peoria Heights, IL,” is comically gruesome about working in a public restroom (I think of it at every movie theatre and rest stop); the second, “Brief Interview #28, Ypsilanti, MI,” is extremely arch and funny about the challenge of long-term relationships: “It’s a total mess.”

Oblivion His last published fiction. Dark, sad and brilliant. Many people love the short, shocking story “Incarnations of Burned Children.” It’ll test your reader’s fortitude. For me, the best stories are: “Another Pioneer,” which is beautiful and eerie—about a kind of Amazon child messiah; you can hear the palm fronds and ambient bugs, feel the great disquiet of encountering something huge; and “The Suffering Channel,” about the length of a novella. Exceptionally funny and sharp, a comic piece about journalism (about which he’s mostly dead on), potential new revenue streams for cable-TV, in-office exercise gear. It’s just amazingly perceptive and funny, with a wonderful restaurant lunch in the middle. My favorite story is “Good Old Neon.” It’s the best story about being a person I know, the pluses and minuses. It’s a sort of update to Tolstoy’s famous story “The Death of Ivan Ilych.” It is unforgettable and something you should read right now.

Consider the Lobster David’s second essay collection. Experiential postcards about politics (his John McCain piece, “Up, Simba,” won a National Magazine award; it’s not so much about the Senator as about how politics works, how reporting on politics works, and ends with a great invitation: “try to stay awake”), sports, 9/11, talk radio. So good throughout it’s hard to pick favorites: it’s like rubbing your chin over a very long pastry cart. “Consider the Lobster,” about a Maine culinary festival, is brilliant, funny, and could de-shell fish you forever. “Big Red Son” is about the awards ceremony for the pornography industry, and is incredibly sharp. (The fans’ “expressions tend to be those of junior-high boys at a peephole, an expression that looks pretty surreal on a face with jowls and no hairline”; and the oddity of seeing video performers faces, strangers’ faces, in sex, “that most unguarded and purely neural of expressions, the one so vulnerable that for centuries you basically had to marry a person to get to see it.”) There’s no non-fiction that gives a better idea of where the country is, what it’s like to live in it now, than this. Unless it’s A Supposedly Fun Thing.

Extra Credit Point 3: Consider also includes, in the great essay on spoken English “Authority and American Usage,” a wonderful description of how hard it can be successfully end a talk. “Suppose you and I are acquaintances,” David writes, “and we’re in my apartment having a conversation, and that at some point I want to terminate the conversation and not have you be in my apartment anymore. Very delicate social moment. Think of all the different ways I can try to handle it: ‘Wow, look at the time’; ‘Could we finish this up later?’; ‘Could you please leave now?’; ‘Go’; ‘Get out’; ‘Get the hell out of here’; ‘Didn’t you say you had to be someplace?’; ‘Time for you to hit the dusty trail, my friend’; ‘Off you go then, love’; or that sly old telephone-conversation-ender, ‘Well, I’m going to let you go now’…in real life, I always seem to have a hard time winding up a conversation or asking somebody to leave, and sometimes the moment becomes so delicate and fraught with social complexity that I’ll get overwhelmed…and will just sort of blank out and do it totally straight—‘I want to terminate the conversation and have you not be in my apartment anymore’—which evidentially makes me look either as if I’m very rude and abrupt or as if I’m semi-autistic…I’ve actually lost friends this way.” It’s stuff like this—impossible to forget, memory graffiti—that makes David’s work feel so warm and aware.

The Pale King David’s last long novel, forthcoming next year from Little, Brown. Excerpts have already run (and can be found) in The New Yorker: it’s a different, older, more powerful Wallace. It’s about IRS agents—not the world’s most charismatic or sympathetic hero squad—learning to accept and embrace their work. It sounds very much like things he talked about in his commencement speech at Kenyon College (published as This is Water) and in conversation. “How much time do I spend doing stuff that actually isn’t all that much fun minute by minute, but that builds certain muscles in me as a grown-up and a human being?” That’s the question all his work—thoroughly, brilliantly, charmingly, and wakefully—sets about answering.

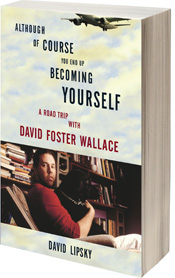

Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace (a Broadway Books trade paperback original; now on sale) |

David Lipsky is the author of

David Lipsky is the author of